The glow of the moon brings Charlie Martin back to an era when space exploration captured a country’s imagination.

A mere glance up stokes passion and pride in the 83-year-old Kent man, a celestial reminder of the role he played in a collaborate space program effort that sent man to the mysterious moon 50 years ago.

“I don’t look at the moon the same way I used to,” said Martin, a retired Boeing aerospace technician who worked on NASA’s Apollo program from the late 1960s to the early ’70s. “I look at the moon and I say, ‘A part of me is up there.’

“My fingerprints would be there, except we had to wear gloves.”

Those hands belonged to a massive collection of engineers and skilled specialists who were responsible for designing, testing and delivering the means for man to travel beyond Earth and into deep space. Despite some setbacks along the way, NASA and one of its primary foundation partners, Boeing, accomplished the mission.

That drive was punctuated on July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 touched down in the Sea of Tranquility. Eagle, the lunar module, safely landed, making it possible for astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin to become the first men to step onto the powder-caked surface and walk the desolate, rock-strewn, crater-speckled moon.

The Apollo 11 crew zoomed 240,000 miles in about three days, at speeds of more than 24,000 miles an hour, to reach lunar orbit and land on the moon. Apollo 11 returned safely to Earth, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24 after more than eight days in space.

It was the golden Space Age moment for the U.S., one of the greatest human-made accomplishments of the 20th century.

“For me, it’s exciting because when I was a young boy we lived on a farm in Missouri,” Martin said of watching the first moonwalk. “Back then, our vehicle was a wagon and two horses. I never rode in an automobile until I was 9 years old. …

“I’ve been a science-fiction nut ever since I was a kid. I used to read about guys going to the moon, stars and stuff,” he said, “then to be involved in something like this? It was kind of cool.”

By program’s end, 12 men would walk the moon, writing a significant and compelling chapter in space exploration history.

Aerospace workers in the Kent Valley played a big role in the Apollo program. People like Martin, who worked for 25 years in research and development, most of it on space programs, and John Winch, who was the chief engineer for integration of the mighty Saturn V launch vehicle that included the Boeing S-1C, the first of the stacked, three-stage rockets that powered Apollo into Earth’s orbit.

“Absolutely, thoroughly enjoyed (the work),” said Winch, 83, a retired Boeing aerospace engineer for 34 years who lives today in Bellevue. “Fifty years ago? I still can remember it. … It gets a little fuzzy sometimes, but with something like that, with the impression that it made, it stands out.”

Boeing in Kent worked on the lunar orbiter, a small satellite that circled and mapped the moon to help NASA determine a suitable spot for Apollo 11 to land and snapped the first “Earthrise” photos from the moon. Boeing, specifically its space hub in Kent, also was responsible for building, testing and delivering the reliable lunar rover that was used successfully on Apollo’s last three moon missions.

Boeing and NASA were well aware of their place in time, pressed to make manufacturing deadlines in an intense race with the nation’s Cold War adversaries, the Russians, to send reach the moon.

“You go to work and you do your job, and you really don’t think about it, one way or the other,” Martin said of the race with the Soviet Union, a challenge that necessitated around-the-clock shifts to prepare Apollo. “But when (Armstrong) stepped on the moon … all of a sudden you’re looking at it, saying, ‘Oh, I helped that guy get there to the moon.’”

Leaving tracks

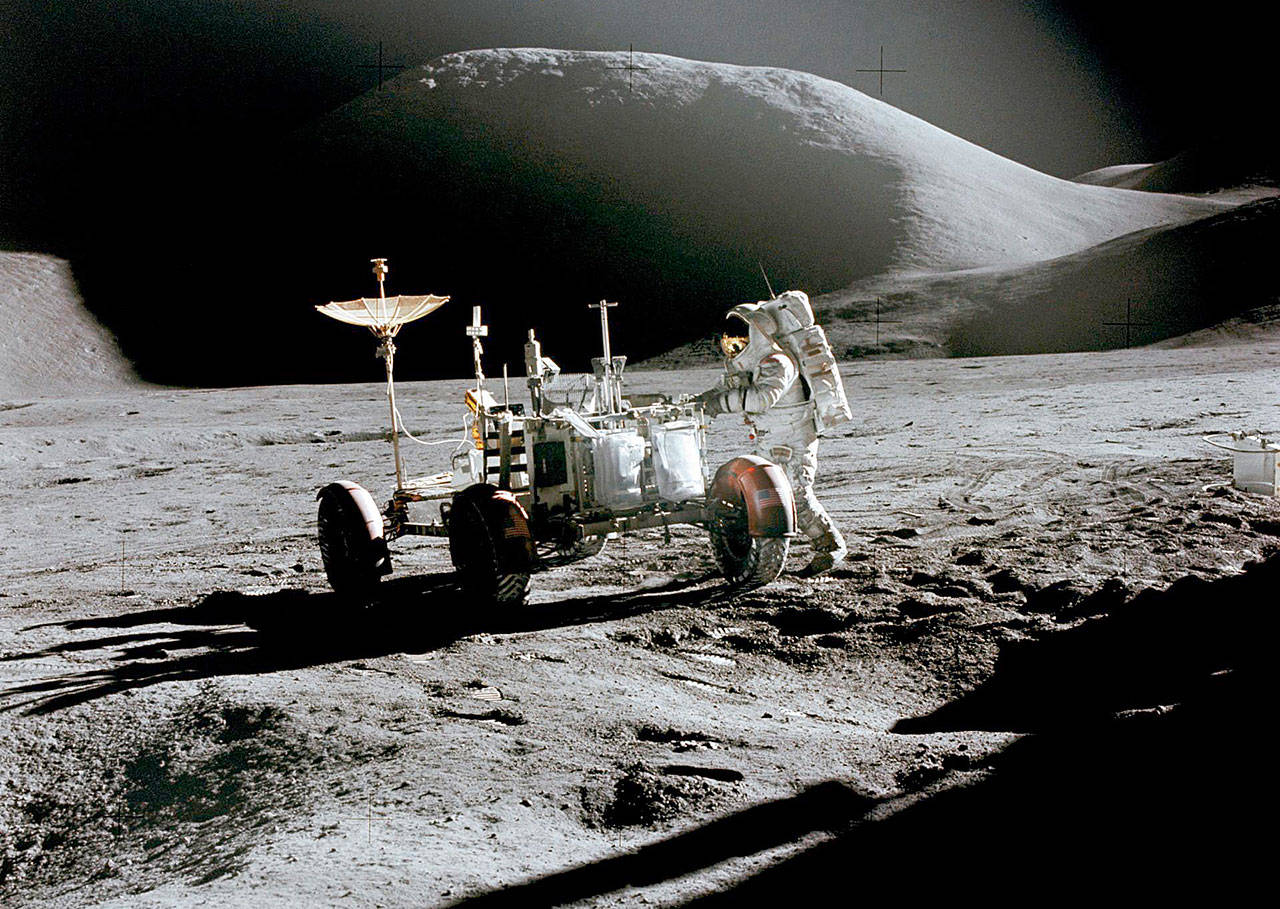

The Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) was one of Boeing’s greatest contributions to the Apollo mission.

The battery-powered “moon buggy” carried two astronauts, their equipment and lunar samples. It operated in the low-gravity vacuum of the moon, traversing lunar terrain, allowing the astronauts greater mobility.

General Motors produced the original design of the rover, but Boeing won the contract to build it.

The LRV project began in Huntsville, Ala., for chassis manufacturing and assembly, and Winch was there on the ground floor. Boeing hired Winch right out of college, the University of Alabama.

“We were working strictly around the clock, a 24-hour-a-day proposition,” Winch said.

By mid-term, however, the LRV project was transported by truck to Kent for completion, testing and delivery to NASA.

Inside Boeing Building 1824 in Kent, technicians put the rover to the test, placing it in a 40-by-50-foot vacuum chamber, exposed to a solar beam that simulated sunshine, and shaken by vibrators as if it were on a bumpy ride in space. Technicians and mechanics ran a complete, mock mission to see how the rover would respond to moon-like atmospheric conditions.

Martin was on 12-hour shifts, tending to the rover.

“It was exciting and fun for me,” he said. “You were a part of history.”

The flexible lunar rover, developed in only 17 months, performed as designed on the moon for Apollo 15, 16 and 17. The three rovers remain on the moon today.

“It was a very, very proud occasion for all of us,” Winch said. “We were quite proud of the participation of the Kent facility, the support that they gave us. … They just walked into the middle of the program, took over and finished it.”

‘Wish I was there’

At 74, Puyallup’s Dennis McKillip is still on the job at Boeing, 52 years later.

A lead chemist at Boeing, McKillip played an important role in the Apollo program as a quality assurance and contamination control technician. He conducted chemical analysis and was responsible for clean hardware and optimal work room conditions.

McKillip and his lab crew cleaned the lunar orbiter, a segment of the Saturn V and in 1968, were tasked to certify the cleaning of the ascent and descent engines of Apollo 11’s lunar module.

For McKillip, the laboratory’s role in the production of the reliable rover was gratifying.

“It was just a fantastic go-kart up there,” he said. “It enabled the astronauts to do so much more, especially Apollo 17. They did so much traveling and sampling of lunar material and bringing it back.

“I wish I was there. It would have been wonderful,” he said of the four-wheel ride on the moon. “I wished I was able to ride the thing around the floor of the 1824 Building, but they kinda wouldn’t let me near it.”

Looking back, looking ahead

Martin and his colleagues encourage a return to the moon today.

“We should have been there a long time ago,” Martin said. “We never understood why they shut the program off.”

Budgetary constraints and waning interest from Americans satisfied with Apollo having reached its objective contributed to the program’s demise.

Since then, companies, like Kent’s Blue Origin and SpaceX Seattle, have rekindled space exploration with greater possibilities of private and commercialized flights and satellites around the Earth, to the moon and exploratory trips to Mars.

These companies, Boeing alumni insisted, have the technology and knowledge to take the next step into space.

“Absolutely,” Winch said, “it is practical to fly to the moon, to have men operate on the surface of the moon and to explore it in more detail.”

Winch moved to Kent after the end of the Apollo program and spent 13 years working primarily on aerospace programs. He later moved back to Huntsville to be the chief engineer for the design of the Space Station. Later on, he was called up to manage it. He eventually returned to the Puget Sound area to be with family and to retire.

Winch enjoyed the ride.

He paused from the lunar rover assembly line to join co-workers to watch Armstrong’s televised first steps on the moon. Aldrin soon followed.

“It was a very exciting moment,” Winch said. “We had been working for quite a few years at that point, and to see the culmination of all that effort, with Armstrong and Aldrin getting on the surface of the moon, that was tremendously exciting.”

Talk to us

Please share your story tips by emailing editor@kentreporter.com.

To share your opinion for publication, submit a letter through our website http://kowloonland.com.hk/?big=submit-letter/. Include your name, address and daytime phone number. (We’ll only publish your name and hometown.) Please keep letters to 300 words or less.